UFC Lawsuit: Expert for Plaintiffs sets damages at up to $1.6 billion

Written by John S. Nash

After a lull in the antitrust lawsuit against the UFC, we now see some activity. Late Friday, the plaintiffs filed their Motion for Class Certification, along with several supporting expert reports and rebuttals, while Zuffa's attorneys filed a Daubert Motion to exclude some of the Plaintiffs' expert testimony. All in all, a few hundred pages of material were filed, so I'll probably spend the next few days going over them in greater detail before posting a more comprehensive summary and analysis. For now, here are a few excerpts that I found immediately noteworthy.

The Scheme

The "Scheme" is how, according to the Plaintiffs, Zuffa attained a monopoly and monopsony over MMA in North America. Reading the Motion for Class Certification I couldn't help but think they had listened to Paul Gift and incorporated his criticisms of what he called "the Carlos Newton."

“The Scheme includes three categories of conduct: (1) Contracts: Zuffa used long-term exclusive contracts with Fighters to limit their mobility and prevent or substantially delay free-agency; (2) Coercion: Zuffa used its market dominance to coerce fighters to re-sign contracts, making its contracts effectively perpetual; and (3) Acquisitions: Zuffa acquired and closed down multiple MMA promoters. The contracts and coercion deprived potential rival MMA promoters of an essential input-the marquee Fighters they needed to compete with Zuffa. The acquisitions eliminated any potential remaining competition . Zuffa became

the “major league” for MMA events and reduced other promoters to “minor leagues.””

Quick reminder that having monopoly or monopsony power is not illegal by itself, but acquiring it and maintaining it through anticompetitive practices is. The Plaintiffs allegation is that Zuffa did the latter.

$1.6 Billion with a B

What quickly caught my attention was the size of the damage estimates by the Plaintiffs' experts. Prof. Andrew Zimbalist came up with a sum of $981 million for the period December 16, 2010 through December 31, 2016, while Dr. Hal Singer came up with an estimate of $811 million at the low end and $1.6 billion at the high end during the period of December 16, 2010 to June 30, 2017, which would place 1,214 Fighters into the affected Bout Class. A third expert for the Plaintiffs, Guy Davis, didn't work on an estimate for damages but instead on how much more Zuffa could have compensated their fighters without impacting their financial obligations. His hypothetical concluded that they could have paid an additional $706 million from December 16, 2010 until the end of 2016 without additional borrowing or equity raises.

Zuffa is obviously contesting these estimates, claiming they are derived from poor models (or even "junk science" in the case of Zimbalist) or irrelevant.

So how did they came up with these estimates? It's hard to know exactly, since most of the reports look like this:

No UFC Union

Zimbalist's estimate is apparently drawn from a comparison between the UFC's pay as a share of revenue and that of boxing, NBA, NFL, MLB, and the NHL.

“My basic methodology is as follows. For each sport that I use as a benchmark, I apply the athlete compensation share of revenue to the reported Zuffa bout revenues to arrive at what Zuffa’s fighters would have been paid if they received the same share as the athletes in these other sports where more competitive labor markets prevail.”

His conclusion is that If the promotion paid a similar share as those sports, fighters would have made an additional $981 million over the 6 year period.

The UFC is contesting Zimbalist's testimony, asking that it be excluded for using a yardstick measure of comparison they refer to as "junk science." Interestingly enough, one of the reasons Zuffa gives for why the comparisons are faulty is that the big four sports leagues’ athletes are in unions.

“Dr. Blair also asserts that the team sport cannot be compared to the UFC, because the athletes in the UFC are independent contractors, have no union, and do not collectively bargain.”

Odd indeed to see the UFC’s attorney blatantly arguing the benefits of unionizing! Zimbalist’s response though is that it’s not unions alone that lead to higher pay but unions ability to better negotiate a more competitive market.

“However, the presence of collective bargaining in the team sports does not undermine their comparability as yardsticks. This is because the primary way that the players’ unions have helped the athletes obtain a larger share of the league’s revenues is by negotiating for rules that increase the ability of athletes to become free agents and benefit from labor market competition.”

Side Note: old time BE members may remember me making nearly identical arguments on here and the now defunct Head Kick Legend site. I can’t take credit for it though, because I came to this reasoning after reading Zimbalist's "Salaries and Performance: Beyond the Scully Model."

Zimablist’s argument regarding the impact of the free agency and the end of the Reserve Clause may be accurate, but that doesn’t mean Zuffa’s attorney’s don’t have a point that comparisons between the UFC and major league sports aren’t that relevant due to their completely different business models. (Boxing, of course, is another matter) Even so, Zimbalist did remind them that Zuffa has made that comparison themselves.

“Zuffa executives have acknowledged in the past the appropriateness of comparing the share of revenues going to athletes in the UFC with professional team sports. When asked what percentage of UFC’s revenue goes to its fighters during a 2012 interview on ESPN’s Outside the Lines, Zuffa LLC’s CEO and co-owner Lorenzo Fertitta stated: “not far off what the other sports leagues pay as a percentage of revenue.” When reminded that the player share in the NBA, NFL, NHL and MLB is around 50 percent, Fertitta replied: “[It’s] in that neighborhood, yeah.” As is clear from the analysis below, Fertitta’s comment is simply

wrong.”

Headliners

Dr. Hal Singer’s estimate is derived from creating a model based on the share of revenue going to pay as compared to: 1) Zuffa from when it was less dominant in the market as compared to more recent, after it foreclosed on competition; and 2) the share of revenue that Strikeforce, a competing promotion, paid its fighters. (Apparently it was 63%.)

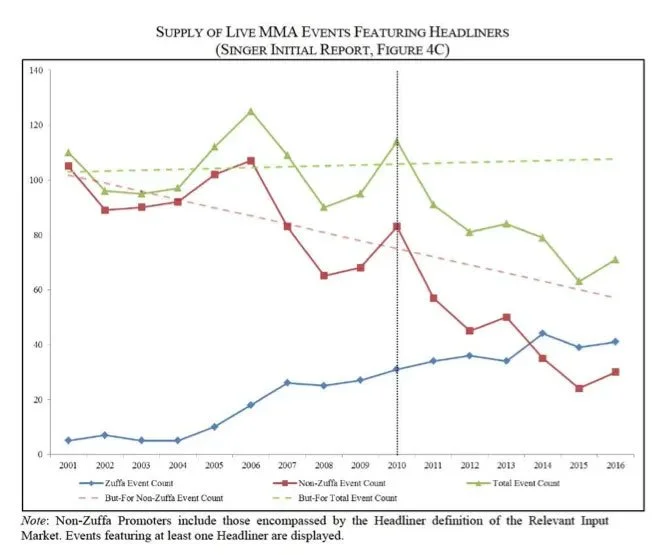

The majority of Singer’s report (that isn’t redacted) is focused on how the UFC foreclosed competition. It’s a long list of putting competitors out of business and locking fighters — especially key fighters — into long term contracts. A major focus of Singer's is Zuffa’s control of what he terms “Headliners.”

“Under the Headliner definition, the Relevant Input Submarket includes the top fifteen Fighters in any of the ten major MMA weight classes, 268 as ranked by FightMatrix. A hypothetical monopsonist over all Headliners could profitably exercise monopsony power,

because non-Headliners are, by definition, lower-ranked Fighters that would typically provide sub-optimal matchups for Headliners.”

(As an aside, I have no idea why the term Headliner needed to be coined when “Championship-Caliber” had been used to identify an almost identical class of boxers in previous antitrust cases.)

So how important are Headliners to Zuffa? Well according to Singer, the “Top of the Card was comprised of Headliners in nearly 80 percent of Zuffa events between 2010-2016.

Moreover, at least one Headliner was at the Top of the Card in 91 percent of Zuffa events from 2010 to 2016.” More specifically, “at least one of the Fighters at the top of the card was ranked first or second. And in 63 percent of these bouts, at least one of the Fighters at the top of the card was ranked in the top five of his or her division.”

Over time we can see how Zuffa became the home to more and more “Headliners,” denying (at least according to the Plaintiffs) other promoters the ability to compete.

To stress the importance of these “Headliners” to an MMA promotion, the Plaintiffs highlight Joe Silva’s deposition:

““Q. And if you have a live MMA Event that doesn’t have a top level, headlining match-up, that could hurt the ability of the event to attract an audience; is that fair?

A. It is. ... You may want a bigger fight for a card, but if people are injured or get married or whatever — you have to work with what you have.

Q. And you’d like to have — as a matchmaker, you’d like to have . . . a complete stable of top-level fighters that are available to fight so you can create headlining events; correct?

A. That would be ideal.

Q. Okay. And you would not headline an MMA event at the UFC with two lesser-known or lower-ranked fighters if you could help it; correct?

A. If you could help it.””

Singer also makes the case that because the UFC was able to lockup such a large share of the “Headliners,” not only did competitors have trouble booking successful events but could not develop new “Headliners” since those were made by facing and defeating current headliners. He uses this as an example of the barriers to entry that the UFC’s has constructed, including some more testimony from Joe Silva to demonstrate Zuffa’s intent.

““if you gave [former two-time Bellator Lightweight Champion Eddie] Alvarez the shot and [UFC Lightweight Champion Benson] Henderson slipped on a banana peel and lost you will have given Bellator he greatest Christmas present of all: Bellator’s champ would jump from number ten to number one. Even just giving their former champion an immediate title shot puts Bellator on a level they don’t deserve.” Silva Dep. at 216:21-217:5; Silva Exh. 16. He further explained that would “benefit Bellator” because “every promotion wants to be able to claim to be number one, to claim that you have the best fighters. That gives some teeth to that claim.””

Singer also alleges that the UFC locks up more fighters than they can actually book, in order to keep them away from rival promoters.

“Zuffa was consistently able to keep Fighters bound by the exclusionary provisions in its contracts—and thus unavailable to other MMA promoters—while simultaneously promoting an insufficient number of bouts given the number of Fighters on its roster. Record evidence indicates that Zuffa was able to suppress the number of events that Fighters would participate below what Fighters would otherwise prefer, and that Zuffa consistently maintained significantly more Fighters under contract than it could use in bouts. In his deposition, Joe Silva testified that, from at least 2010 to 2015, he had “been complaining to managers and fighters and others” that Zuffa “had more fighters under contract than [Zuffa] had fights to give them.”Silva also testified that he kept Fighters under contract who he otherwise would have cut; his rationale was to keep these Fighters away from Bellator. Kurt Otto, President and founder of a now defunct MMA promotion called the IFL, testified that it was his perception that Fighters at Zuffa were “collecting dust.” Record documents discuss the “shelving” of Fighters by Zuffa.”

Signing more fighters than you can book seems problematic when the average MMA career of a UFC fighter is 8.9 years, according to Zuffa’s own expert, Dr. Topel. That 8.9 years, of course, is their whole professional MMA career and not just their UFC career, which is much, much shorter according to Singer.

“The median career duration for a Zuffa Fighter at Zuffa—typically the apex of a Fighter’s career—is 0.82 years; the average is 2.00 years. I also performed similar calculations for Fighters in the Relevant Input Market and Submarket. As seen below, the median duration of Fighter careers ranges from 0.38 years to 1.33 years; the average duration ranges from 1.80 years to 2.55 years. Accordingly, Dr. Topel’s 8.9-year statistic is driven by Fighters when they are outside the Relevant Input Market and Submarket—in other words, it is capturing the portion of a Fighter’s career spent in the minor leagues.”

(Speaking of minor league, it is alleged in Singer’s report that “ONE Championship also offered itself as a ‘feeder organization to UFC.’” The source for this claim was redacted.)

As part of Singer’s comparison between Zuffa when it was dominant in the market versus today, he analyzed Fighter compensation as a percentage of Event Revenue over time. His finding was that the percentage of Event Revenues going to Fighters decreased as their share of the market increased.

“In fact, my initial report demonstrated that increases in Fighter compensation over time have been swamped by increases in Zuffa’s Event Revenue per Fighter, indicating that Fighter compensation has failed to keep pace with increases in Fighter productivity—a clear indication of the exercise of monopsony power.”

"Zuffa had the financial wherewithal to pay its fighters substantially more"

As mentioned earlier, Guy Davis’s estimates are not for damages resulting from the UFC’s “Scheme” but instead an analysis of Zuffa’s finances and a determination if they could have compensated the fighters more without impacting their financial obligations and without additional borrowing or equity proceeds. He then came up with a bunch of scenarios where Zuffa paid the Fighters of share of the revenues anywhere from 33% to 38%.

““From 2005 to 2016, and at all times during the Class Period, Zuffa had the financial wherewithal to pay its fighters substantially more than the amounts it actually paid. Zuffa’s exceptional revenue growth, profit margins, and borrowing capacity afforded management and equity holders the ability to forgo a portion of their discretionary distributions, excessive aviation expenses, and management fees to pay fighters a higher compensation. This hypothetical shift to increased fighter compensation would have had no impact on Zuffa’s ability to honor its financial obligations to its non-fighter employees or third-party creditors.””

The results for Davis’s 38% scenario appears to be that Zuffa could have been able to compensate the Fighters for an additional $708 million and remain a “financially healthy” company. It would nice to know exactly how Davis came to this conclusion, but almost his entire report and rebuttal have been redacted.

Based on what little of his analysis we have though, we can try and estimate what percentage of the revenues the fighter were receiving during the period Davis used (12/16 /2010-12/31/16). According Zuffa’s July 2016 Lender’s presentation, the promotion had $2.409 billion in revenue between 2011-2015. For 2016, it is thought their revenues were a little over $700 million. This would mean that the Fighters received around 17% of Zuffa’s revenues as their compensation.

Zuffa is asking that Davis testimony be excluded, claiming that Zuffa’s capacity to increase “compensation is not relevant” to whether there was an antitrust violation and “would mislead a jury.”

“It also does not require special competence to conclude that successful business owners could reallocate funds from one category of expenses to another.”

But what about that $1.6 billion?

I know many people are going to focus on the damage estimates given and wonder if it’s possible that the Fighters could be awarded that much. The answer is yes, it is possible. Potentially even more. If the case goes to trial and the judge or jury decides in the Plaintiffs’ favor, then the damaged are trebled (become three times as large). So if $1.6 was awarded, that would become $4.8.

But — this is a pretty big but — that’s a long way away and it’s much more probable that even if they receive damages it won’t be for those amounts. First, the class has to get certified (which is what they filed a motion for Friday.) If it doesn’t get certified, then to continue with the suit, the plaintiffs will have to either file individual cases or a mass tort. And even if they are successful with class certification, it is much more likely there will be a settlement (which will surely be much lower than the damage estimates given) before it ever gets to a trial decision.

It’s also important to remember that this is the Plaintiffs’ experts’ reports, so we shouldn't be surprised that the evidence presented weighs heavily against Zuffa. They'll have a chance to make their case soon enough. But if in the end the suit makes it all the way to trial and the plaintiffs are awarded damages in the hundreds of millions, or even billions, Zimbalist already has a suggestion as to how it should be paid.

“Zuffa’s 2016 sale price of over $4 billion to WME-IMG is more than enough to pay for damages. Zuffa’s owners made that $4 billion by systematically underpaying fighters.”

*This article originally appeared on Bloody Elbow. It was written by John Nash on Feb. 19, 2018